Mortality in Staffordshire Bull Terriers

Perceptions of health issues in dogs are frequently based on anecdote and hearsay and many ‘facts’ are unsupported by adequate scientific evidence. This applies to virtually all breeds and the Staffordshire Bull Terrier is no exception. It is regrettable that such data was not gathered several decades ago by the veterinary profession although there are now attempts to address this failure with studies of dogs attending surgeries being undertaken via computerised links.

To its credit the Kennel Club did try to address this lack of information by conducting the large health survey covering all breeds in 2004, but overall this was disappointing as making meaningful conclusions and comparisons were virtually impossible. It was conducted by issuing questionnaires to clubs to distribute to their members and returns were purely voluntary. The response rate for Stafford owners was rather low at 15.7% and only 117 deaths, including age and cause, were reported. The median age at death was found to be 12.8 years which is around what was perhaps to be expected, based on owners’ experience. Analysis of causes of death was attempted but with the small numbers involved this was limited. Perhaps the only significant finding was that cancer was considered to be the cause of death in 44.4% of cases, but the median age was virtually the same as the overall figure.

As canine health is now a major issue, Breed councils and clubs are being encouraged to undertake studies and continuing monitoring of their respective breed’s state of overall health. Inevitably the way such studies are conducted will vary from breed to breed, depending on several factors. What can be done with a numerically large breed, such as Staffords may be impractical with a ‘small’ one and vice versa. For example in some breeds with only a limited number of litters being born annually, following every puppy born throughout its life is being attempted. This is clearly impossible with Staffords where the best course of action is to study a representative sample which will permit the extrapolation of any findings across the whole breed.

As the results of the KC study were limited, a larger study was undertaken on the age and causes of death in Staffords – this was published in 2013.

Information was obtained from owners and breeders on five hundred and seventy eight Staffords dying from 1995 onwards by paper or on-line questionnaire, or by face to face or telephone interview. All had been born and lived their entire lives in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland. For each dog the following information was ascertained: name (usually pet name), KC registered or not, age at death in years, cause of death, neutered or not, and euthanized or died naturally. Owners were also asked if the dog had ever had any skin lumps and, if so, what was the diagnosis. The responses to this question formed the basis of a separate study, which has already been published, and are irrelevant to the present one unless the skin lump was malignant and contributed to the dog’s death.

Of the dogs, 226(39.1%) were male and 352(60.9%) female, aged from less than one year old to 18 years of age. 530(91.7%) were KC registered and 48(8.3%) unregistered. Overall 53.3% (308/578) had been neutered but there was considerable difference between the sexes: 73.0% (257/352) of bitches had been spayed but only 23.0% (52/226) of dogs had been castrated. 441(76.3%) had been put to sleep to prevent further suffering, 114(19.7%) died naturally and 23(4.0%) from ‘unnatural’ causes such as road traffic accidents.

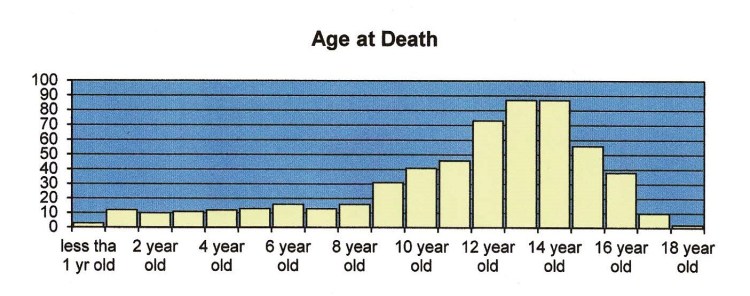

Figure 1 – Numbers dying by age in years.

Figure 1 presents the numbers dying on an age by year basis. The mean (average) age at death was 11.9 yrs, with the median being 12.5 yrs, and the mode (age with the most deaths) 13 yrs and 14 yrs (equal). Small differences between the sexes, and whether neutered or not, were found. With dogs, the mean age was 11.4 yrs but if castrated this rose to 12.1 yrs; if those that had died of causes that were not natural, such as trauma, were excluded these ages rose to 11.8 yrs and 12.3 yrs respectively. With bitches, a similar pattern was found although ages were greater than with the dogs. The overall bitch mean was 12.2 yrs but this rose to 13.0 yrs in those that had been spayed, however excluding those not dying naturally little increase was found, the respective figures being 12.3 yrs and 13.0 yrs. The mean age of those dogs put to sleep was 12.0 yrs which is virtually the same as the overall mean of 11.9 yrs, and similarly for dogs that were KC registered it w as 11.8 yrs. The proportion of dogs dying under ten years old from all causes was 23.9% (138/578) and this is discussed further below.

From fig 1, it may be seen that the number of dogs dying starts to increase at nine years old which is late middle-age for Staffords, leading into ‘old age’ which may be considered as being ten or more years of age. Although some dogs inevitably died prematurely, the pattern of increase in deaths, peaking at 12-14 years, is one to be expected with a basically healthy breed. The absence of any peak of deaths at a younger age, as occurs with some other breeds, suggests that no condition causing significant numbers of premature deaths is present in the breed.

An analysis by cause of death was conducted. This presented certain problems as it often depended on owners’ recall and vets may not have given a specific diagnosis. Nevertheless every attempt was made to classify causes of death as accurately as possible on the information supplied. ‘Old age’ was considered to be a bona fide cause for dogs of advanced years that just died or simply faded away in the absence of any specific condition being diagnosed. All cancers, irrespective of type or site, are included under the one heading but non-malignant conditions were classified by bodily system or region involved. For example, brain tumours were included with cancers but brain haemorrhages were placed in ‘neurological’. Results are presented in table 1. Conditions that did not fit in the various classifications, and were not common, were grouped under ‘miscellaneous’.

Table 1 Numbers dying by cause.

Cause Number

Old age |

194 (33.4%) |

Cancer |

199 (34,4%) |

Thoracic |

28 (4.8%) |

Neurological |

37 (6.4%) |

Skeletal |

17 (2.9%) |

Gastric |

12 (2.0%) |

Renal |

22 (3.8%) |

Miscellaneous |

41 (7.1%) |

Unnatural |

19 (3.3%) |

Cause not given |

9 (1.6%) |

Total |

578 (100%) |

Cancers and old age accounted for just over one third of all deaths each. All dying of old age were, as was to be expected, over ten years old and most were older than twelve years. Cancers, in general, tend to increase with age and may be regarded as part of the aging process. Thus it was no surprise to find that three quarters of dogs dying with cancer of some form or another were over ten years.

The types of cancer reported were wide ranging, affecting most areas of the body although numbers for most were very low. However, more than ten cases of six different specific types were reported and these are presented in table 2. With the exception of brain tumours and mast cell tumours, these were predominantly in old dogs.

Table 2 Types of cancer causing the death of more than ten dogs.

Type |

|

|

Number |

% All Deaths |

% all cancers |

Brain |

|

|

31 |

5.4 |

15.6 |

Oral |

|

|

11 |

1.9 |

5.5 |

Stomach |

|

15 |

2.6 |

7.5 |

|

Bowel |

|

|

15 |

2.6 |

7.5 |

Mast Cell Tumour |

|

13 |

2.2 |

6.5 |

|

Mammary |

|

13 |

2.2 |

6.5 |

|

Of the 28 dying of thoracic conditions, all but two were cardiac in nature, eleven with heart attacks, although the diagnosis is frequently vague as sudden deaths are often diagnosed as such without further investigation, and fifteen with heart failure. Neurological conditions accounted for 37 deaths. Seventeen were fits; eleven cases of epilepsy, three of L-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria (L-2-HGA) and three were of an unspecified nature.

Of the L-2-HGA cases, two were in dogs born before DNA testing was available but the third case occurred in a very young dog born after routine testing had been put in place and was thus totally preventable. Eleven died of cerebral vascular accidents, mainly brain haemorrhages, and one had dementia. Five dogs in the neurological category were euthanized with temperament problems although one was, in fact, not really aggressive to humans but was over-boisterous around children and could easily have caused an accident. Two of the remaining four may have had clinical problems that were not fully investigated.

Seventeen dogs had skeletal problems and fifteen of those involved spinal conditions, often as an aftermath of injury, while the remaining two were euthanized with severe arthritis. Gastric problems, apart from cancers, caused the death of only twelve dogs, six of which had liver failure, but on the other hand 21 of 22 dogs with renal problems died of kidney failure and the remaining one had a bladder condition.

As the name suggests, the miscellaneous section comprised 44 dogs dying of diverse conditions that did not fit in easily with the other groupings. Of those eleven died during surgery or the result of surgical complications; eight with endocrine conditions of which six had Cushings syndrome; eight with an infection; three with pyometra; four with a fatal internal haemorrhage; seven with haematological or immune system conditions; one with seasonal canine disorder and the remaining two were of a complex multi-system nature.

Of the nineteen dogs dying of causes that were not natural, five had been involved in a road traffic accident, eight had been poisoned, and six had been involved in some other sort of accident. With nine dogs, the cause of death was not stated.

Table 3 lists those non-malignant conditions from which ten or more dogs died.

Condition |

|

|

Number |

% Total |

Heart Attack |

|

|

11 |

1.9 |

Heart Failure |

|

|

15 |

2.6 |

Epilepsy |

|

|

11 |

1.9 |

Cerebral Vascular Accident |

11 |

1.9 |

||

Spinal Problems |

|

15 |

2.6 |

|

Renal Failure |

|

|

21 |

3.6 |

Surgery Related |

|

11 |

1.9 |

|

As stated above, 138 of the 578 dogs in the study died when less than ten years of age. Such deaths may be deemed to be premature and it is thus important they are investigated for any cause that is particularly prevalent. However 31 deaths occurred in nine year olds which appears to be the point that death rates increase as age takes its toll. Under nine years old, the numbers dying from all causes in each year age group varied from ten to sixteen. Table 4 lists the conditions considered to be the cause of death for five or more dogs under ten years of age. For all other causes of death, the numbers dying less than ten years old were very small and as most of these were usually low in all ages, no analysis was possible.

Table 4 Causes of death for five or more dogs under ten years,

Condition Number % Total <10yrs

Brain tumour |

|

16 |

11.6 |

|

Mast cell tumour |

|

5 |

3.6 |

|

Heart attack |

|

6 |

4.3 |

|

Epilepsy |

|

|

7 |

5.1 |

Temperament problem |

5 |

3.6 |

||

Spinal problem |

|

6 |

4.3 |

|

Surgery related |

|

9 |

6.9 |

|

Poisoning |

|

7 |

5.1 |

|

Cause not stated |

|

7 |

5.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As may be seen from table 4, brain tumours were the most common cause of premature death, accounting for 11.6% of deaths in dogs under ten years old and more than 50% of all such deaths as only 31 cases were reported for all ages. While further investigations are clearly needed, these findings suggest that brain tumours could be an important cause of premature death in Staffords. Although the clinical presentation is variable, temperament changes may be present. Thus if a dog’s nature changes, especially if a previously docile dog starts to show increasingly aggressive tendencies, a brain tumour should be considered and investigated rather than having a dog simply euthanized as having a bad temperament with all its implications. The only other malignancy in table 4 is mast cell tumours, all in dogs of five or more years of age. This condition was discussed in depth in the previously published report on skin lumps where it was recommended that all skin lumps are fully investigated as rapid surgical removal is essential in the more severe forms of the condition.

Six were considered to have had heart attacks but the vague nature of this diagnosis has been discussed above. Epilepsy normally has an early onset in young dogs so finding seven with the condition aged less than ten at death, out of a total of eleven in the study, was to be expected. Life spans of affected dogs depend on the severity and frequency of fits and the continuing success of the long term treatment necessary to contain the condition, but sadly some have to be euthanized at a comparatively early age.

Of the remaining conditions in table 4, temperament problems have been discussed above while the rest are not really age related. Three of the spinal problems were specifically associated with trauma and its long term effects, which could happen at any age, while trauma cannot be totally discounted in the remaining three cases on the limited clinical information available. The remaining two causes listed, surgery-related and poisoning, are neither breed nor age associated. Surgery always carries some degree of risk and sadly the occasional dog will die when under anaesthetic or from post surgery complications. Given the inquisitive nature of all dogs, poisoning (hopefully accidental) is an ever present threat to dogs of all ages.

The Kennel Club health survey of 2004 comprised only 117 Stafford deaths whereas the present one has just less than five times as many thus giving better overall data. One difference was that the KC study reported cancers as the cause of death in 44% of cases and old age for 23%, whereas the present one gives figures of 34% and 33% respectively, although the combined totals of both categories are identical, accounting for two thirds of all death reports in each study. The reason for these apparent differences is probably due to owner interpretation of information supplied by their vet. Many old dogs may have some form of cancer when they die but do not actually die from the condition. The danger is that Staffords may be considered to be at greater risk of cancer based on inadequate data. ‘Cancer’ is a collection of many different malignant conditions and the various forms would need to be studied individually to ascertain any specific breed susceptibility. The scatter of other conditions considered as causes of death in the KC study were similar to those reported here although the numbers were much less and further comparison is impossible.

The present study shows that Staffords are a healthy breed overall. Life expectancy is about twelve years although bitches may live a little longer than dogs on average and neutered dogs and bitches would seem to live longer than those remaining entire. Although some dogs may die earlier and some may live longer, owners can reasonably expect their Staffords to live for twelve to fourteen years based on the figures presented here. Premature deaths are a matter for concern for any breed of dog and it was good to note that there was no ‘spike’ of deaths around any particular age, as happens with some breeds, with a specific condition being responsible. Causes of premature death were varied as can be expected with all breeds of dogs and indeed any species of animal. The only conditions in Staffords that may need to be monitored are brain tumours and mast cell tumours. Vets are almost certainly aware of the latter although not all undertake full clinical investigations to assess the grade of the tumour and thus prognosis. With brain tumours, further studies should be undertaken to confirm the diagnosis, rather than basing this on clinical grounds, and to determine specifically the type of tumour; it is also important to consider a brain tumour in dogs with temperament changes. A problem encountered in the present study was the dependency on owners’ recall and perception of the causes of death of the dogs they reported, often several years later, plus any information (or lack of) given by any vets involved. Prospective on-going studies to monitor future trends need to be considered, although veterinary on-line projects such as VetCompass and SAVSNET may in time be able to supply information on the causes of death in all dogs, whether pure bred or not.

Inherited Conditions Affecting Staffords

The following hereditary conditions have been found to affect Staffords although the prevalence of each is low.

Juvenile Hereditary Cataract (HC)

• Bilateral progressive cataracts leading to total blindness, usually by 18-24 months old

• Early formation of the cataracts may be seen by ophthalmological examination around eight or nine weeks old.

• Around five to eight months old, opacity of the lens becomes apparent to the naked eye.

• Affected dogs require surgery to remove cataracts and restore sight.

• Cause is a defective recessive autosomal gene, HC-HSF4.

• Carriage rate in untested dogs is approximately 5%.

• All dogs being bred from should be genetically tested to determine if they are carriers of the gene unless hereditarily clear.

• Two carriers must not be mated together as each puppy has a 25% chance of being affected and going blind, and a 50% chance of being a carrier.

• If a carrier is used for breeding to a clear specimen, each puppy has a 50% chance of being a carrier and the breeder should test all puppies for their carrier status before re-homing.

Persistent Hyperplastic Primary Vitreous (PHPV)

• PHPV is the failure of the embryonic blood supply to the eye to wither away and disappear completely by the time of birth. It is thus congenital and may be unilateral or bilateral.

• Severity varies from very mild with little material, perhaps only a few dots, remaining behind the lens, to more severe with greater amounts of residual material being present.

• Mild cases are not progressive and affected dogs are not visually impaired, but in more severely affected dogs, cataracts and other complications impairing sight may develop.

• The condition is hereditary but the genetic mode of transmission has not yet been described.

• A single eye test at any time from six or seven weeks old will give a definitive diagnosis of affected or unaffected,

• All dogs being bred from should have had an eye examination, which will cover PHPV, at some stage before mating.

• Affected dogs should not be bred from, even if only mildly affected, as there is the risk of progeny being more severely affected.

• Breeders should, wherever possible, have whole litters tested at six or seven weeks old to determine status prior to re-homing.

Posterior Polar Sub-capsular Cataract (PPSC)

• A different form of cataract from HC and may be described as punctuate or star-like.

• Has been reported in many breeds including SBT’s.

• Incidence in SBT’s is unknown but is probably low on current eye test reports.

• May develop at any time from six months to seven years old or even later,

• Most cases are non-progressive with the cataract remaining limited with little, if any, sight impairment but in a small number of cases the cataracts enlarge resulting in sight problems.

• It has been suggested that it may be caused by an autosomal dominant gene but this requires verification.

• Any dog used for breeding should have had an eye examination within the previous twelve months, in case PPSC has developed since any previous test.

• Any dog found to be affected should not be used for breeding.

L-2-Hydroxyglutaic Aciduria (L-2-HGA)

• A neurometabolic condition characterised by high levels of L-2-Hydroxyglutaric acid in plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, urine and all body fluids.

• Cause is a recessive defect in the autosomal gene, L2HGDH, which prevents the normal metabolisation of L-2-Hydroxyglutarate.

• The neurological system is affected with pathological changes in the brain.

• Signs include seizures, unsteady gait, tremors, muscle stiffness exacerbated by exercise, altered behaviour and dementia. These may worsen as the dog gets older.

• Carriage rate in untested dogs is about 15%.

• All dogs being bred from should be genetically tested to determine if they are carriers of the recessive gene unless hereditarily clear.

• Two carriers must not be mated together as each puppy has a 25% chance of being affected, and a 50% chance of being a carrier.

• If a carrier is used for breeding to a clear specimen, each puppy has a 50% chance of being a carrier and the breeder should test all puppies for their carrier status before re-homing.

The U tube video demonstrates the effect this debilitating condition has on the Stafford.